But Oedipus was troubled, for she would say no more, but only held his hand, and when he drew it away it was wet with her tears. Then he thought in his heart, “Verily my mother would not weep for naught. What if, after all, there be something in the tale? I will go to the central shrine of Hellas and ask the god of Truth, golden-haired Apollo. If he say it is a lie, verily I will thrust it back down that coward’s throat, and the whole land shall ring with his infamy. And if it be true—the gods will guide me how to act.”

So he set forth alone upon his pilgrimage. He drew near to the sacred place and made due sacrifice, and washed in the great stone basin, and put away all uncleanness from his heart, and went through the portals of rock to the awful shrine within, where the undying fire burns night and day and the sacred laurel stands. And he put his question to the god and waited for an answer.

Through the dim darkness of the shrine he saw the priestess on her tripod, veiled in a mist of incense and vapor, and as the power of the god came upon her she beheld the things of the future and the hidden secrets of Fate. And she raised her hand toward Oedipus, and with pale lips spoke the words of doom, “Oedipus ill-fated, thine own sire shalt thou slay.”

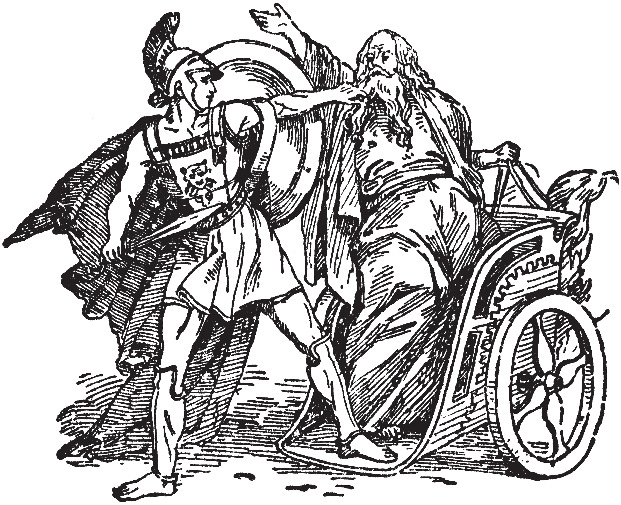

As she spoke the words his head swam round like a whirlpool, and his heart seemed turned to stone; then, with a loud and bitter cry, he rushed from the temple, through the thronging crowd of pilgrims down into the Sacred Way, and the people moved out of his path like shadows. Blindly he sped along the stony road, down through the pass to a place where three roads meet, and he shuddered as he crossed them; for Fear laid her cold hand upon his heart and filled it with a wild, unreasoning dread, and branded the image of that awful spot upon his brain so that he could never forget it. On every side the mountains frowned down upon him, and seemed to echo to and fro the doom which the priestess had spoken. Straight forward he went like some hunted thing, turning neither to right nor left, till he came to a narrow path, where he met an old man in a chariot drawn by mules, with his trusty servants round him.

“Ho, there, thou madman!” they shouted. “Stand by and let the chariot pass.”

“Madmen yourselves,” he cried, for his sore heart could not brook the taunt. “I am a king’s son, and will stand aside for no man.”

So he tried to push past them by force, though he was one against many. And the old man stretched out his hand as though to stop him, but as well might a child hope to stand up against a wild bull. For he thrust him aside and felled him from his seat, and turned upon his followers, and, striking out to right and left, he stunned one and slew another, and forced his way through in blind fury. But the old man lay stiff and still upon the road. The fall from the chariot had quenched the feeble spark of life within him, and his spirit fled away to the house of Hades and the Kingdom of the Dead. One trusty servant lay slain by his side, and the other senseless and stunned, and when he awoke, to find his master and his comrades slain, Oedipus was far upon his way.

On and on he went, over hill and dale and mountain stream, till at length his strength gave way, and he sank down exhausted. And black despair laid hold of his heart, and he said within himself, “Better to die here on the bare hillside and be food for the kites and crows than return to my father’s house to bring death to him and sorrow to my mother’s heart.”

But sweet sleep fell upon him, and when he awoke hope and the love of life put other thoughts in his breast. And he remembered the words which Merope the queen had spoke to him one day when he was boasting of his strength and skill.

“Strength and skill, my son, are the gifts of the gods, as the rain which falleth from heaven and giveth life and increase to the fruits of the earth. But man’s pride is an angry flood that bringeth destruction on field and city. Remember that great gifts may work great good or great evil, and he who has them must answer to the gods if he use them well or ill.”

And he thought within himself, “’Twere ill to die if, even in the uttermost parts of the earth, men need a strong man’s arm and a wise man’s cunning. Never more will I return to far-famed Corinth and my home by the sounding sea, but to far-distant lands will I go and bring blessing to those who are not of my kin, since to mine own folk I must be a curse if ever I return.”

So he went along the road from Delphi till he came to seven-gated Thebes. There he found all the people in deep distress and mourning, for their king Laius was dead, slain by robbers on the highroad, and they had buried him far from his native land at a place where three roads meet. And, worse still, their city was beset by a terrible monster, the Sphinx, part eagle and part lion, with the face of a woman, who every day devoured a man because they could not answer the riddle she set them.

All this Oedipus heard as he stood in the market place and talked with the people.

“What is this famous riddle that none can solve?” he asked.

“Alas, young man, that none can say. For he that would solve the riddle must go up alone to the rock where she sits. Then and there she chants the riddle, and if he answer it not forthwith she tears him limb from limb. And if none go up to try the riddle, then she swoops down upon the city and carries off her victims, and spares not woman or child. Our wisest and bravest have gone up, and our eyes have seen them no more. Now there is no man left who dare face the terrible beast.”

The End, Part Three